How to write and publish a scenario for Call of Cthulhu

John Hedge

Are you someone who enjoys writing? Are you a long-time GM wondering if, perhaps, others would enjoy the stories you craft in your spare time? Do you like the idea of creating something beautiful and putting it out there in the world?

At the Miskatonic Playhouse, we’ve put together this handy FAQ, answering many of the questions you might have when writing for the best investigative TTRPG around.

What, who, how?

Unlike fantasy roleplaying games, where generally the game master is expected to do a large portion of the world-building themselves, investigative roleplaying games have a long history of published scenarios.These are generally, short, contained mysteries with a textbook style breakdown of the investigation, as well as some helpful handouts that the Keeper can read and use in order to run the investigation.

While Chaosium publishes their own scenarios, there are also third-party publishers creating content for the game. At present, Chaosium allows anyone to publish scenarios for Call of Cthulhu (CoC), through the Miskatonic Repository (MR) on drivethrurpg.com.

Find Chaosium’s explanation of the MR here

Do I have to use the Miskatonic Repository?

Basically, no. But in reality, yes.

Call of Cthulhu is based on the Cthulhu Mythos, much of which is in the public domain. And, so long as you write something that doesn’t contain monsters owned by someone else, and don’t make any references to the rules of CoC, you can publish your own scenarios however you like. There are also other Cthulhu-based systems with their own licenses and rules you can look into.

However, in reality, people who go it alone find that they sell fewer copies and make far less money from their scenarios than those who do publish through the MR. In addition, Chaosium is quite supportive of the MR, selling some of the titles at conventions and generally doing a decent job supporting community content, answering questions and occasionally publicising breakthrough scenarios. So even though you are splitting your royalty share with Chaosium, you generally make more money doing so than going it alone.

Is publishing on the MR a good way to make some cash?

No. Of the over 1000 scenarios published on the MR, it’s likely that only the dozen or so top selling scenarios have made their authors a reasonable return. Writing community content is only for:

New authors who want to learn to write and are looking for a supportive place to learn the skill.

Hobbyists happy to spend some money turning their ideas into pretty little books.

Authors writing ‘for the love of it’.

Setting expectations

One of the reasons a lot of authors start writing for the MR is that they hope to make their hobby ‘cost neutral’ or at least, to offset some of the costs of their addiction to buying RPGs. The idea being that they write scenarios and sell them, spending the money on buying more scenarios. Honestly, nearly any other income stream is probably more viable. You are likely to put upwards of a hundred hours into the production of your first scenario, and if you make $50 from your first attempt, you’ll be doing quite well. You could be better paid doing nearly anything else. Avoid this trap.

You’re saying it will cost me money?

Not necessarily, but spending money gets you access to all sorts of useful shortcuts. You get to cut out the boring bits of publishing and do the fun bits of writing.

For instance:

Paying for a pretty front cover is an excellent way to get people’s attention and sell a scenario. A good front cover can cost between $50-$150 of a professional artist's time, but it’s a great way to get your scenario noticed in a crowded field.

If you are a newer author and want to learn, there’s a lot to be said for partnering with an editor who can read through your work. We talk more about editors further down.

Paying someone well-versed in layout to turn your boring manuscript into an eye-catching booklet.

Buying a course like the Storytelling Collective Write your first adventure module is a formalised way to go from a blank piece of paper to a published scenario and helps a lot of writers navigate this complex road.

The Miskatonic Playhouse is also for sale! Pay us a little bit of cash to jump the queue and hear our lovely team run an Actual Play of your scenario.

Most authors try at least once to do the whole thing themselves. But eventually discover there are some things they are good at, and others they are just not built for. And, if they can afford it, often end up paying for professional help. Or agreeing to split their proceeds with others.

Remember: While there is a lot of money in TTRPGs, it’s often focused in the hands of big companies (cough Hasbro cough). By spending your money on independent artists, editors, and podcasts you get to directly support your community, having them do the boring bits of editing and production, letting you enjoy the experience of writing and publishing. Hell, someone might even ask you to sign a copy of your scenario at your next con!

What does a scenario usually contain?

A good scenario starts with an Introduction explaining what the reader is about to experience, it gives an overview of the whole story and provides context to the reader. It is normally written in order to sell the scenario to the reader and entice them to keep reading.

The author then moves onto the Keepers Information. This section contains important context for the scenario. It explains everything upfront, making sure the reader has all the context for what will happen in the following pages. Never hide information from the reader. It is a textbook, not a story.

Next comes the Dramatis Personae. The cast of non-player characters. This is for the reader to understand who each person is, somewhere for them to reference back to when they’re reading the rest of the scenario. A good picture helps bring the characters to life.

The bulk of your scenario will be the Investigation. In this section the author walks the reader through the scenario step-by step. Starting with a Hook that gives the investigators a reason to investigate the mystery, a number of locations filled with clues that give insight into the mystery and some kind of finale or climax where the investigators face the monster, or the result of its work.

Try and remember throughout that you are writing a guide for someone running a game. Not telling a story.

Finally, an Appendix contains:

Important additional information and context the didn’t fit in the main text.

Stat blocks for all NPCs & Monsters.

Large print-friendly versions of any handouts or maps.

Pre-generated investigators.

While pre-generated investigators aren’t technically a requirement, these days they are absolutely considered essential and you are encouraged to take the time to design a group of pre-generated investigators that suit the investigation and have the skills to at least solve, if not survive, the mystery.

You do not have to follow this structure. Many scenarios don’t. However, in our experience, it’s better to learn to write to the style of investigations already out there until you learn why you want to do things differently.

How long should my scenario be?

While the scenario should contain all the relevant information needed to run a game, figuring out that balance can often be tricky for newer authors. When in doubt, cut it out.

Most scenarios aimed at being run in a single session are between 6,000-15,000 words. If this is your first scenario, you should be trying to write a short scenario closer to 6000 words. Someone has to read the whole thing in order to play it with their friends. You are doing them a service by keeping it short and clear.

A common mistake is for the author to get excited about a certain time period or location and want to share all of their background research with the reader. If you absolutely must, you can include some of these elements in an Appendix section, but keep the bulk of this background out of your main scenario. The scenario also needs to be referenced during the game, so if it’s short and clear, then it’s far easier to use.

I know that Gen AI is banned, but what about this other specific use of AI?

When it comes to creativity, Gen AI is garbage. It is not the future of writing, and it does not make your work better when you pass your work through ChatGPT. For all kinds of scenarios, but especially in complex mysteries with many interlocking parts, these AI models are not your friend.

Even if we’re going to ignore the environmental costs and the inherent theft that is the training data, we still come back to the core issue: AI generated work sucks.

When people realise that you are using AI generated content in your games, you will find yourself quickly unwelcome in every major community space. If Chaosium realises you have published AI generated content in your game, they will take it down. It’s not worth it.

All of that being said, even well-meaning people might fall foul of AI checkers by, for example:

Asking a friend to do an edit pass and the friend just passes it through ChatGPT.

Licensing a photo through a reputable website and discovering there is AI generated material in it.

Collaborating with a group and discovering that not everyone understands that they can’t copy-paste material from ChatGPT.

What is not happening, although you hear people claiming regularly, is original work being flagged as AI generated.

If you realise that your work is compromised, go back to the latest version you are sure is entirely written by your hand and start working from there.

What makes a scenario sell well?

If you are a completely unknown writer, you are relying on capturing strangers' attention. You have a limited number of ways of doing that.

When you list your scenario on Drivethru, then customers will only see a small thumbnail of the front cover beside a long list of other thumbnails. If it looks nice, they can click through and read about it. It’s unfair, and unreasonable, and feels a little unpleasant, but the reality is that if you are an unknown author, the biggest chance you have of capturing people’s attention is with an impressive or intriguing front cover.

This is all you get for your advertising. Can you use it well? Two of these scenarios have sold thousands. Can you guess which?

Once the front cover has pulled them in, you have two tools to sell a scenario to them: The blurb and the free preview. Both of which you should use. In the blurb, people want a simple way of understanding what they are buying, and if you can give that to them, they’re more likely to buy it. Figuring out how to pitch is an entire art in of itself. In the free preview, customers see the first few pages of your scenario and might skim the introduction. If they immediately know what it’s about and are excited about it, they’re more likely to buy it.

Customers are more likely to buy scenarios if they:

Are cheap and seem like good value for money.

Have elements the customer is already familiar with.

Think their group will be able to use the scenario.

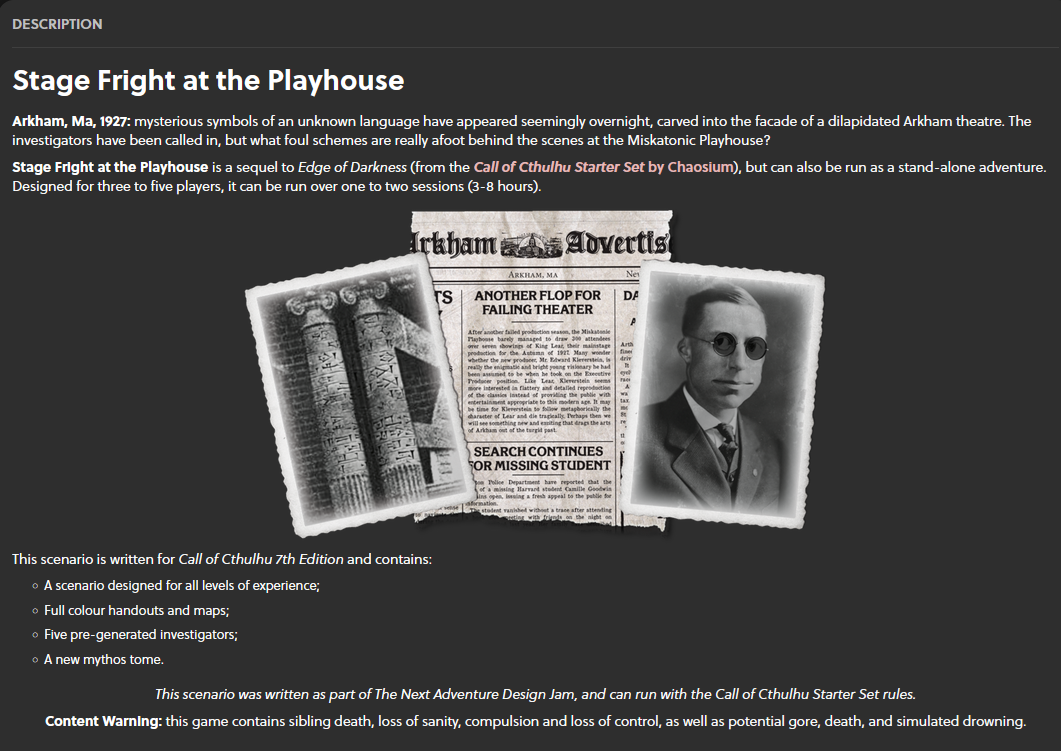

This is the description for Stage Fright, which has sold hundreds of copies. What aspects of the description do you think made that true? The time period? The pictures? The fact that it seems easy to use?

Watch out! You might be tempted to make your scenario really cheap so as to sell it easily. The thing is, customers tend to associate price with quality and if you step too far outside of the regular pricing structure, they’ll assume your product is trash. The generally agreed cost of a scenario is 15-20¢ per page (in American dollars). Try not to stray too far from that number.

A one-shot scenario set in 1920s Arkham County that seems easy to use, but with a unique twist, is going to be an easier sell than a semi-futuristic alternative reality, post-apocalyptic horror campaign.

Still confused? Try this easy sales tactic: Can you describe your scenario as “like X but Y”? Where X is a popular scenario, movie or similar, and Y is the cool twist you’ve put on the material.

The other way of selling a scenario is through name recognition and word-of-mouth. Which, as an unknown author, basically means having friends who are happy to spend money on you. After you’ve published a few scenarios and many people have seen your work, this becomes more and more important as people begin associating your name with quality scenarios. But this is a long and slow process.

So what makes a good front cover?

A good front cover is an art and not easily explained.

One common approach is to try and replicate the style of Chaosium. The font Cristoforo is the best match on the market, (though it needs to be licensed with a one-off payment of $9.99). You then place your title in yellow around a box and your art is a semi-realistic drawing in the style of John Sumrow or Sam Lamont.

Another is to try and create something beautiful by working with a talented artist to bring about your own vision. There are very few guidelines on the MR so if it’s unique and eye-catching, it’s likely to at least get people to take a look.

Finally, the most common approach from newer authors is to use public-domain images and some filters to create something appropriately atmospheric. Chaosium has a set of art packs of public domain work that can be found here and a ton of additional resources in their extended guidelines here.

I want to use a Mythos monster, but I’m not sure if I’m allowed to or not. How do I find out?

The Cthulhu Mythos is a vast and confusing place. Many different authors have contributed to it. Some of those authors are long dead, their work now in the public domain and you are free to use it. Others are alive and well and quite protective of their intellectual property.

When working inside the MR, Chaosium wants you to use everything they have access to. That includes all the monsters, grimoires, artefacts, and other goodies in the various Chaosium books. They are also happy for you to use material they have created, such as the investigator character sheets.

Sometimes Chaosium might have an agreement with an author’s estate that does not extend to the MR. Sadly it is up to you to figure out the difference and there is no simple list anywhere of which monsters are ‘safe’ to use in the MR and which are not. Here however, are some guidelines:

If the monster first appeared in an H.P. Lovecraft story (Like C’thulhu, the Colour out of Shape, or the Deep Ones) then you are definitely able to use that monster.

If the monster appears in a Chaosium book (Such as the Keepers Rulebook), but there is a ‘Used with permission’ line for that monster in the acknowledgements section, then that monster is probably not ok to use.

If the monster appears in a Chaosium book and there is no ‘Used with permission’ line for that monster in the acknowledgements, then that monster is probably ok to use.

The most common monster that newer writers fall foul of are the ‘Hounds of Tindalos’, which are licensed to Chaosium, with permission from the Frank Belknapp estate. This means that the Hounds of Tindalos cannot be used in a published MR scenario as Chaosium doesn’t have the right to offer that.

Other authors to look out for are monsters created by Ramsay Cambell or Brian Lumley. Both of whom have specifically opted out of licensing their creations to the MR. You cannot use monsters from their books.

Still unsure? There is a strong tradition of taking the concept of a monster created by an author and changing its name and aspects of it to create your own version of that monster. Give it a new creepy name, center it in a new location and make it your own. That’s how Lovecraft did it.

If you do mess up: Don’t worry. If you’ve published a monster you are not allowed to and it is flagged, Chaosium will email you asking you to take it down and remove the offending materiel from your scenario. So long as you comply and it was clearly an error, no-one will mind. However, repeat offenders will quickly find themselves banned from publishing with the MR.

I’m told I need an edit. What does that actually mean?

Editing is where someone looks over your work and provides suggestions and feedback on it. For TTRPGs, we tend to break it up into three types of editing:

Developmental editing focuses on the scenario as it might play out. A developmental edit is about how the information is delivered, what actually happens, and might involve changing the story so that it makes more sense. Words like plot, character development, and pacing are bandied about.

Copy editing focuses on creating the best possible version of the manuscript that already exists: sentences might be rewritten for clarity; word choice and grammar are critically examined; comments about your overuse of the em-dash appear; overly ambitious attempts to use colons and semi-colons may be reined in.

Proofreading is the final step, where someone reads it focused solely on spotting errors. This step is almost entirely about removing spelling mistakes and grammatical errors.

In the MR, editors often also act as mentors for newer authors. They can help the author bring about their vision, help them avoid classic mistakes and produce a scenario that is far more likely to be played by the community.

They can also often support authors by setting deadlines and making you feel safe to move on to publication.

The MP in-house editor is John Hedge. You can find him on our Discord. He’s always happy to chat and will look over your work for free, as well as offering more in-depth, paid options.

A quick note: sometimes in horror you are dealing with sensitive subjects. An editor or reader might suggest a sensitivity edit or sensitivity pass. This is often done when an author is writing about a subject they don’t have direct experience of and wants to make sure they haven’t said or done something that might upset people with that experience. Sensitivity readers tend to be specialised and from the communities in question. So you might have to hunt around to find the right person.

Do I actually need to playtest? I can’t get a group together.

If you want to write scenarios for Call of Cthulhu, you should probably get some experience playing Call of Cthulhu. Part of that means figuring out a way to play some games. It doesn’t have to be in person. There’s a huge community online and lots of people keen to play games. If you’re struggling to recruit people for your games, try taking part in some online games and make friends. Then people are more likely to want to play with you.

We really recommend trying to play Call of Cthulhu if you want to write for it. You begin to understand which bits of information are relevant and which aren’t when you are running games yourself for different groups. And then when you do run your playtests, it really helps you understand how players actually react to the material. All of this will improve your writing.

Finally, and probably most importantly, playing games should be fun! If you aren’t enjoying the experience of running your scenarios, how do you expect others to do so? Use yourself as a guinea pig to see what works, what’s fun, and what is not.

Struggling to find playtesters? The Miskatonic Playhouse is always for hire and can run a closed playtest or a public Twitch stream of your game.

I’ve seen that some of the scenarios get printed into books. How does that work?

If your scenario reaches Electrum best seller on Drivethru (251 sales), then Chaosium will review it and may decide to approve it for Print on Demand (POD). A lot of authors really prize POD, because it allows them to get a physical copy of the thing they wrote.

Printing a book takes quite a bit more effort than throwing a PDF out onto the web and if you get selected, then you will be contacted by a Chaosium rep to walk you through the process.

Very occasionally, a book will be selected for POD before it hits Electrum. This is almost always because the author/s are well-known, are already connected to Chaosium, and have previously sold successful scenarios. It’s also not uncommon for Chaoisum to reject scenarios for POD if the author has a poor reputation and has clearly cheated the system in order to reach 251 sales. And once you’ve gained a reputation as a cheat, it’s not an easy one to shake.

You keep suggesting I should work with others, how do I find them?

Chaosium has a great resource, the Creators Helping Creators sheet full of people who have volunteered their services to the MR.

You can also just ask around. The Miskatonic Playhouse Discord server is full of talented creators who love helping out and you’re likely to find people there willing to offer a little bit of help for free and then a lot more help for a fair price.

Not sure about Discord? There’s a Miskatonic Repository Facebook group where you can also ask for help too.

Finally, the lovely Bridgett Jeffries and Nick Brooke are only an email away. They work directly for Chaosium and it’s their job to help you out.